Low atmospheric pressure

The Martian atmosphere is composed mainly of carbon dioxide and has a mean surface pressure of about 600 pascals, much lower than the Earth's 101,000 Pa. One effect of this is that Mars' atmosphere can react much more quickly to a given energy input than can our atmosphere.[16] As a consequence, Mars is subject to strong thermal tides produced by solar heating rather than a gravitational influence. These tides can be significant, being up to 10% of the total atmospheric pressure (typically about 50 Pa). Earth's atmosphere experiences similar diurnal and semidiurnal tides but their effect is less noticeable because of Earth's much greater atmospheric mass.

Although the temperature on Mars can reach above freezing (0 °C), liquid water is unstable over much of the planet, as the atmospheric pressure is below water's triple point and water ice simply sublimes into water vapor. Exceptions to this are the low-lying areas of the planet, most notably in the Hellas Planitia impact basin, the largest such crater on Mars. It is so deep that the atmospheric pressure at the bottom reaches 1155 Pa, which is above the triple point, so if the temperature exceeded 0 °C liquid water could exist there.

Wind

The surface of Mars has a very low thermal inertia, which means it heats quickly when the sun shines on it. Typical daily temperature swings, away from the polar regions, are around 100 K. On Earth, winds often develop in areas where thermal inertia changes suddenly, such as from sea to land. There are no seas on Mars, but there are areas where the thermal inertia of the soil changes, leading to morning and evening winds akin to the sea breezes on Earth.[17] The Antares project "Mars Small-Scale Weather" (MSW) has recently identified some minor weaknesses in current global climate models (GCMs) due to the GCMs' more primitive soil modeling "heat admission to the ground and back is quite important in Mars, so soil schemes have to be quite accurate. "[18] Those weaknesses are being corrected and should lead to more accurate assessments going forward but make continued reliance on older predictions of modeled Martian climate somewhat problematic.

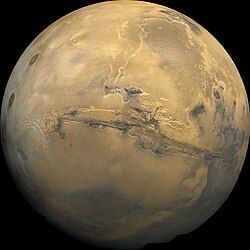

At low latitudes the Hadley circulation dominates, and is essentially the same as the process which on Earth generates the trade winds. At higher latitudes a series of high and low pressure areas, called baroclinic pressure waves, dominate the weather. Mars is dryer and colder than Earth, and in consequence dust raised by these winds tends to remain in the atmosphere longer than on Earth as there is no precipitation to wash it out (excepting CO2 snowfall).[19] One such cyclonic storm was recently captured by the Hubble space telescope (pictured below).

One of the major differences between Mars' and Earth's Hadley circulations is their speed[20] which is measured on an overturning timescale. The overturning timescale on Mars is about 100 Martian days while on Earth, it is over a year.

Effect of dust storms

2001 Hellas Basin dust storm

Time-lapse composite of the Martian horizon during Sols 1205 (0.94), 1220 (2.9), 1225 (4.1), 1233 (3.8), 1235 (4.7) shows how much sunlight the July 2007 dust storms blocked; Tau of 4.7 indicates 99% blocked. credit:NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell

See also: Mars dust#Atmospheric dust

When the Mariner 9 probe arrived at Mars in 1971, the world expected to see crisp new pictures of surface detail. Instead they saw a near planet-wide dust storm[21] with only the giant volcano Olympus Mons showing above the haze. The storm lasted for a month, an occurrence scientists have since learned is quite common on Mars. As observed by the Viking spacecraft from the surface,[14] "during a global dust storm the diurnal temperature range narrowed sharply, from fifty degrees to only about ten degrees, and the wind speeds picked up considerably---indeed, within only an hour of the storm's arrival they had increased to 17 meters per second, with gusts up to 26 meters per second. Nevertheless, no actual transport of material was observed at either site, only a gradual brightening and loss of contrast of the surface material as dust settled onto it." On June 26, 2001, the Hubble Space Telescope spotted a dust storm brewing in Hellas Basin on Mars (pictured right). A day later the storm "exploded" and became a global event. Orbital measurements showed that this dust storm reduced the average temperature of the surface and raised the temperature of the atmosphere of Mars by 30 °C.[15] The low density of the Martian atmosphere means that winds of 40 to 50 mph (18 to 22 m/s) are needed to lift dust from the surface, but since Mars is so dry, the dust can stay in the atmosphere far longer than on Earth, where it is soon washed out by rain. The season following that dust storm had daytime temperatures 4 °C below average. This was attributed to the global covering of light-colored dust that settled out of the dust storm, temporarily increasing Mars' albedo.[22]

In mid-2007 a planet-wide dust storm posed a serious threat to the solar-powered Spirit and Opportunity Mars Exploration Rovers by reducing the amount of energy provided by the solar panels and necessitating the shut-down of most science experiments while waiting for the storms to clear.[23] Following the dust storms, the rovers had significantly reduced power due to settling of dust on the arrays.

Dust storms are most common during perihelion, when the planet receives 40 percent more sunlight than during aphelion. During aphelion water ice clouds form in the atmosphere, interacting with the dust particles and affecting the temperature of the planet.[24]

It has been suggested that dust storms on Mars could play a role in storm formation similar to that of water clouds on Earth.[citation needed] Observation since the 1950s has shown that the chances of a planet-wide dust storm in a particular Martian year are approximately one in three.[25]

Saltation

The process of geological saltation is quite important on Mars as a mechanism for adding particulates to the atmosphere. Saltating sand particles have been observed on the MER Spirit rover.[26] Theory and real world observations have not agreed with each other, classical theory missing up to half of real-world saltating particles.[27] A new model more closely in accord with real world observations demonstrates that saltating particles create an electrical field that increases the saltation effect. Mars grains saltate in 100 times higher and longer trajectories and reach 5-10 times higher velocities than Earth grains do.[28]

Cyclonic storms

Hubble, colossal Polar Cyclone on Mars

First detected during the Viking orbital mapping program, cyclonic storms similar to hurricanes have been detected by various probes and telescopes. Images show them as being white in color, quite unlike the much more common dust storms. These storms tend to appear during the northern summer and only at high latitudes. Speculation is that this is due to unique climate conditions near the northern pole.[29]

Methane presence

Methane has been detected in the atmosphere of Mars by ESA's Mars Express probe at a level of 10 nL/L.[30][31][32] Since breakup of that much methane by ultraviolet light would only take 350 years under current Martian conditions, some sort of active source must be replenishing the gas.[33] Mars' current climate conditions may be destabilizing underground clathrate hydrates but there is at present no consensus on the source of Martian methane.

Carbon dioxide carving

Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter images suggest an unusual erosion effect occurs based on Mars' unique climate. Spring warming in certain areas leads to CO2 ice subliming and flowing upwards, creating highly unusual erosion patterns called "spider gullies".[34] Translucent CO2 ice forms over winter and as the spring sunlight warms the surface, it vaporizes the CO2 to gas which flows uphill under the translucent CO2 ice. Weak points in that ice lead to CO2 geysers.[34]